Decompression Sickness (DCS)

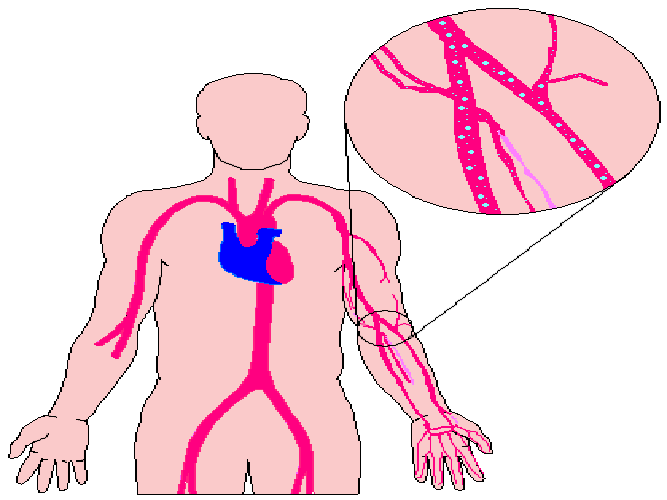

The current thinking is that bubbles exist to some degree in the body after all dives. If the bubbles are few and small, they have no effect, but if they exist in quantity, their volume can be large enough to cause decompression sickness. Generally, bubbles must be within poorly perfused tissues or on the arterial side of the circulatory system to cause DCS.

Bubbles on the venous side are generally harmless, so gas phase must either develop on the arterial side, or it must move by some mechanism from the venous side to the arterial side, or both. Because bubbles can develop in or be carried to practically any part of the body, decompression sickness can be characterized by dozens of seemingly unrelated symptoms with varying severity. This means that diverse factors may theoretically predispose you to DCS, and other factors may be protective – again in theory.

Hyperbaric physicians readily recognize some signs and symptoms as DCS, but others that present themselves after a dive may or may not be DCS. In many types of DCS, the exact injury mechanism – beyond gas phase formation – is a mystery. As an example, it’s still unclear what causes limb and joint pain in DCS. The reason for the difficulty is that the interaction between gas phase and tissues can be complex. Physiologists theorize that effects include irritation to blood vessel walls and multiple biochemical processes. Bubbles may stimulate blood platelets to congregate and cause local clotting. It is possible that the immune system attacks bubbles as it would an infectious invader with a host of defensive cells, enzymes and other responses.

All of these processes make DCS more complicated than the simple mechanics of bubbles blocking blood flow to tissue. Despite the different signs and symptoms, and the questions about what specifically causes them, the various manifestations of decompression sickness tend to share some characteristics. Decompression sickness tends to be delayed after the dive, and may take as long as 36 hours to manifest, though about half of DCS cases appear within an hour of the dive. When diving with helium, however, DCS often appears quickly, and the victim may have symptoms while still decompressing; this is very rare with air/EANx, unless the diver has skipped a substantial amount of deeper decompression.

Decompression sickness can worsen over the first few hours after onset. Based on these facts, a physician would know that a symptom appearing 48 hours after a dive, or one Encyclopedia of Recreational Diving The Physiology of Diving that appears shortly after a dive but quickly improves without any first aid or treatment, is likely not DCS (although other diagnosis is still required). Physiologists have traditionally designated decompression sickness as either Type I (nonserious, pain-only) or Type II (serious, involving central nervous system) based on the symptoms present in a patient. More recently, some physiologists have proposed a Type III (serious, interaction between AGE and DCS) as well. Each of these types has subcategories of specific DCS based upon signs and symptoms.

Although classifications are useful for studying DCS, in a clinical setting they’re less important because they often don’t delineate the immediate seriousness of a case. For instance, a diver with both tingling fingertips and a diver paralyzed from the waist down would likely be suffering from Type II DCS. Furthermore, it’s possible to have multiple signs and symptoms. Type I DCS Type I decompression sickness is pain-only DCS that presents signs and symptoms that are not immediately life-threatening or likely to cause immediate long-term disabilities. That said, physiologists still don’t understand all the mechanisms that occur when bubbles form in your body, so begin first aid and seek prompt medical care if you or a fellow diver exhibits signs or symptoms of even Type I DCS. Cutaneous Decompression Sickness. Bubbles coming out of solution in skin capillaries can cause cutaneous decompression sickness, also called skin bends. A red rash in patches, usually on the shoulders and upper chest, characterizes cutaneous DCS. It is more common in chamber “dives” than in actual dives in water, so some physiologists think that inert gas flow through the skin may be involved. Although cutaneous decompression sickness is not considered serious by itself, its presence indicates decompression problems and the possibility of more serious symptoms.

If no other symptoms present, doctors may treat the patient entirely with oxygen breathing and without recompression. Joint and Limb Pain Decompression Sickness. Joint or limb pain occurs in approximately 75 percent of DCS cases. As mentioned, the cause of joint pain is unclear. Tests show that merely having a gas space in your joints doesn’t cause pain, and can occur naturally in nondiving circumstances. Physiologists propose different mechanisms for the resulting pain, including bubble growth within bone marrow, or bubbles irritating tendons and ligaments. Since the pain is stationary in some victims and moves over time in others, it’s likely that multiple Reference PADI Rescue Diver Video Encyclopedia of Recreational Diving The Physiology of Diving The Physiology of Diving mechanisms exist for joint and limb pain. Joint and limb pain symptoms may be found in more than one place on the same limb, such as the shoulder and elbow; bisymmetrical symptoms are unusual. Like cutaneous decompression sickness, limb pain decompression sickness is considered serious, at least in the short term, primarily because it may progress to more severe forms of DCS.

PADI Encyclopedia of Diving